Reuters Breakingviews - The process of working out sovereign debts is not working. Countries such as Zambia are twisting in the wind because of long delays in restructuring their borrowings. It is harder to get all creditors to agree now that China is a big lender. A more integrated approach that better manages laggard lenders could lead to swifter results.

The Group of 20 large economies thought they had solved the problem of disjointed debt talks when they created the “

common framework” in 2020. Until then, rich Western countries had renegotiated loans to struggling developing countries via the “Paris Club” while China had gone its own way. The new idea was to bring the key government creditors together in one group when dealing with the poorest debtor nations.The results have been disappointing. Zambia, which has $24 billion in foreign borrowings and defaulted in 2020, still hasn’t finished restructuring its debts. Sri Lanka, which has $52 billion in external debt, and Ghana, which has $29 billion, are also in limbo. Both defaulted in 2022.

Drawn-out debt negotiations can debilitate a country. Investors don’t want to pour in new money. People flee the country to look for better lives elsewhere. What’s more, the longer it takes to jump-start an economy with a debt deal, the less creditors are likely to get back.

Other developing countries such as Egypt and Pakistan are drowning in debt. While the situation isn’t as bad as it was during the last big crisis 25 years ago, a combination of high interest rates and weak global growth is forcing many countries to cut back on investments that could help drag them out of poverty and build low-carbon infrastructure.

GRIDLOCK

Despite its name, the common framework isn’t comprehensive: it only covers the poorest countries. That is why Sri Lanka, which has middle-income status, cut separate deals with the

Paris Cluband

China. What’s more, the framework only covers official loans rather than private sector debt, which is often a big slice of the total.

The normal process is for a debtor country first to negotiate a deal with the International Monetary Fund, which provides emergency financing if the government makes economic reforms and agrees a restructuring deal with its official creditors. Private sector bondholders and banks come in later.

The common framework does not ensure fairness between different classes of creditor. The Paris Club says debtors must “seek” comparable treatment from their other lenders. But it has never torn up a deal when it ends up with worse terms than another creditor, as is often the case.

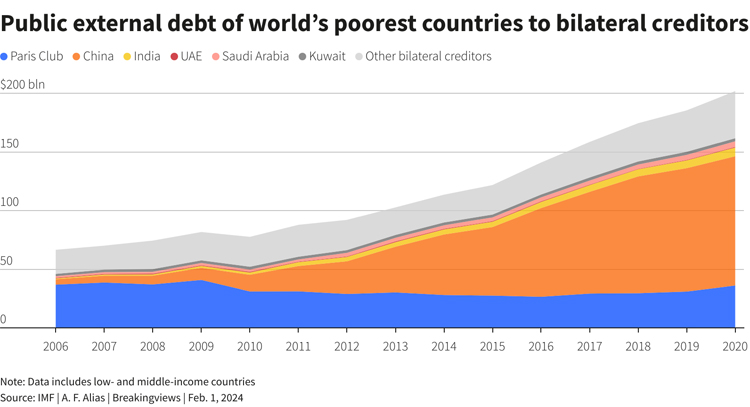

The growing involvement of China, which lent

$1.3 trillion to developing countries as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, has further complicated matters. This is partly because the People’s Republic never accepts a reduction in the face value of loans that turn sour.

Beijing may agree to lower the net present value (NPV) of the debt by cutting interest rates and extending maturities. This is what happened with Zambia, where all the official creditors accepted a 38% NPV cut. But China has not disclosed the NPV reduction it agreed with Sri Lanka. Nor have the official creditors disclosed the

deal they agreed with Ghana in January.

The suspicion is that Beijing’s refusal to take big haircuts is determining the approach of all official creditors. Private lenders fear they will have to accept bigger losses to make the defaulting country’s overall debt sustainable. If not, there won’t be a proper debt restructuring and the state will limp on until the next crisis.

Sri Lanka’s bondholders have

complained about the lack of transparency in the country’s deals with official creditors, and have yet to restructure their own debts. But the worst example of a breakdown in trust came in Zambia. The government in Lusaka agreed a deal with bondholders last November which involved a similar reduction in NPV to what it had secured from official creditors. But those lenders, including China,

torpedoed the deal. The private creditors are now up in arms and Zambia is still in limbo.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

One solution to this cat’s cradle of problems would be to turn the common framework into a comprehensive one. Not only would middle-income countries such as Sri Lanka be part of the scheme. Private creditors would join official ones to negotiate the broad outlines of a deal at the start of debt talks.

Hung Tran of the Atlantic Council argues that this would speed up the process, foster trust between different groups and make it easier to agree deals that treated all creditors similarly. Sean Hagan, the former IMF general counsel, has proposed a

similar idea

Another proposal is to tighten up the rules on “comparable treatment”. Lee Buchheit, a veteran legal expert in sovereign debt, says the first group of creditors to agree a deal could ask for a “most favoured creditor clause”. This would ensure that if another creditor got better terms, those which had already signed a deal could get the same sweeter arrangement.

Paris Club creditors could propose this approach if they were prepared to take a big haircut, but China was not. If Beijing still didn’t come into line, the borrower would either have to offer the rich countries a better deal or stop servicing its Chinese loans. The snag is that few heavily indebted countries will be willing to risk Beijing’s wrath, as it is often their biggest trading partner.

Yet another option would be for Western countries to take a big unilateral haircut. While this would let China off the hook, the cost would be fairly low if the deal was with countries such as Ghana which owe less to the People’s Republic than to Western creditors. In selective cases, this could make geopolitical sense at a time when the United States and China are fighting for influence.

It is not in rich countries’ financial or political interest for more poor nations to get stuck in the debt vortex. Whether they use a mix of these ideas or something different, their workouts need to improve.