September, 9, 2025

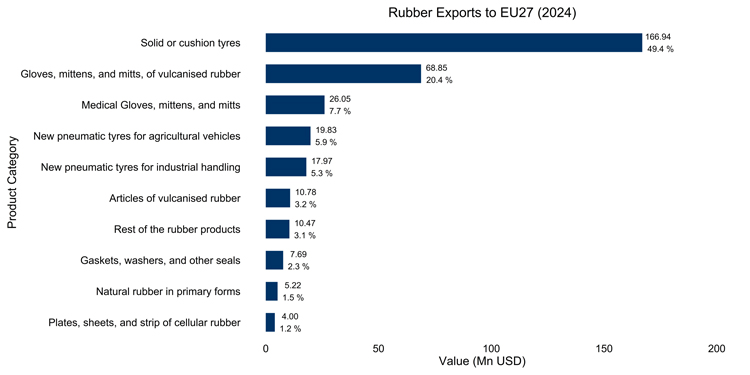

The European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) takes effect on 30 December 2025. This regulation aims to prevent deforestation associated with seven commodities—cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soy, wood, and natural rubber—and products derived from them, such as tyres, chocolate, and wooden furniture. Any product exported to the EU market must be deforestation-free, legally produced according to the laws of the originating country, and traceable to the specific plot of land where it was sourced. In 2024, Sri Lanka exported 27 different rubber and rubber-based products at Harmonised System six-digit (HS-6-digit) to the EU worth USD 337.79 million (Mn). These products include solid or cushion tyres, gloves, mittens and mitts, new pneumatic tyres, and articles of vulcanised rubber (Figure 1). The EU remains a significant destination for these value-added exports, emphasising the importance of meeting EUDR requirements.

Source: Authors’ illustration using data from Trade Map, ITC.

Between 2022 and 2024, Sri Lanka exported an average of USD 329 million worth of EUDR-covered products to the EU annually, with natural rubber products accounting for 97.5% of this value.

Compliance with EUDR: Challenges

The European Commission’s benchmarking system employs quantitative and qualitative criteria to classify countries. Quantitative drivers include deforestation rates, land expansion for agricultural purposes of commodity crops like rubber, and commodity production tendencies. Qualitative drivers assess the effectiveness of legal frameworks, enforcement mechanisms, transparency, land-use planning, and anti-corruption measures. Countries with good environmental governance and low deforestation will be ranked as low-risk and will only face 1% of operator audits, while high-risk countries are audited at 9%. Standard-risk countries, which constitute the middle category, are subjected to 3% controls and are not covered under simplified procedures.

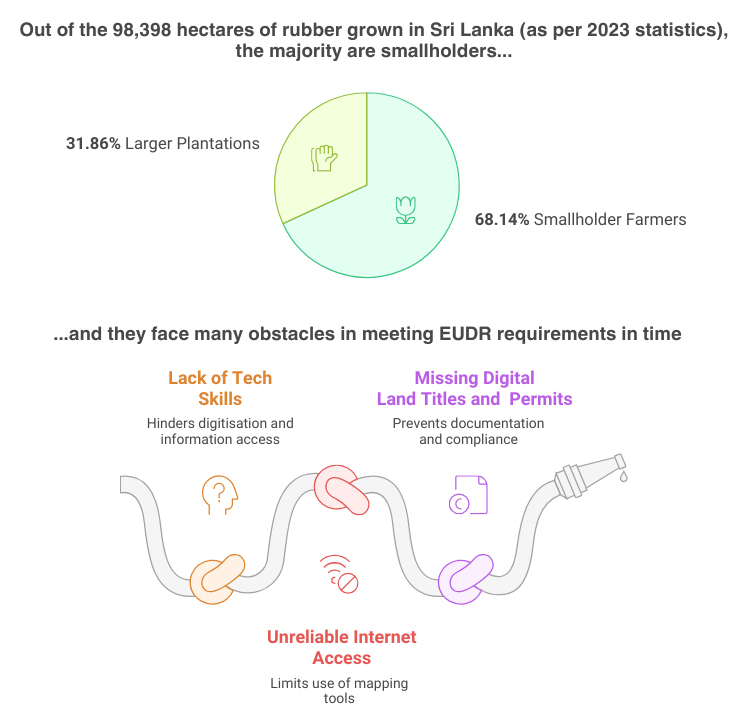

While Sri Lanka is classified as a low-risk country under the EUDR—meaning that EU importers will not need to conduct risk assessments—exporters must nevertheless submit detailed geolocation data and proof of legal land ownership for farms producing these commodities. For large plantations, providing the necessary proof can be a straightforward process. However, smallholder farmers, who manage 68.14% of the country’s total 98,393 hectares of rubber cultivation area (Figure 2), face much greater challenges, especially in obtaining technological support with digitisation and in supplying land ownership information in the required digital format. Smallholders often lack reliable internet access, smartphones, and the technical skills needed to use mapping tools. Many do not possess digitised land titles or permit documentation.

These limitations create a risk that EU buyers will prefer large-scale suppliers who can more easily comply, potentially excluding small farmers from a high-value market.

Source: Authors’ illustration using data from the Rubber Development Department and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs).

The economic costs of EUDR to Sri Lanka are significant. Modelling suggests that compliance costs, estimated at a 5% rise in the price of exports, would reduce rubber exports to the EU by 7.6%, or USD 24.4 million annually. A scenario of complete non-compliance would shut the EU market for Sri Lanka’s rubber exports to the EU, which could shrink the GDP by 0.07%. It is important to emphasise that the GDP loss resulting from the EUDR non-compliance is significant, especially considering the substantial tariff shocks resulting from the US tariffs. The primary reason for this noteworthy GDP impact is the high domestic value added within the rubber sector, as raw materials are primarily sourced from local farmers. Additionally, the US tariff shock would reduce wages by -0.94%, compared to the EUDR effect of -0.47%. A reduction in factor prices reduces the negative impact of the tariff shock substantially, by reallocating resources to other sectors. In the event of non-compliance, the reduction in labour demand from the rubber industry is a significant 15.6%. In 2023, the rubber manufacturing sector employed 34,048 workers. Male workers accounted for 75.6% of the sector’s labour force, while female workers accounted for 25.4%. A 15.6% contraction in labour demand results in 5,312 fewer workers demanded by the industry. Under the assumption that job vulnerability will be proportionate, 4,013 men and 1,299 women will face direct employment vulnerability.[1]

Sri Lanka’s Readiness: Progress and Gaps

Sri Lanka has made several attempts to increase EUDR preparedness, especially in the rubber industry. The Survey Department and Rubber Development Department have begun a GIS-based mapping scheme of smallholder rubber plantations with a deadline for completion by end 2025. The farmers are being given QR codes linking them to geolocation data, ownership, and permit status so that buyers can scan and verify them to prove that the rubber supplied had been obtained in accordance with Sri Lankan law. But progress remains slow, according to key informants from the industry. Staff shortages are slowing down mapping work, record-keeping is still manual, and internet connectivity in rural areas where rubber is grown is often unreliable.

Learning from Global Best Practices

Other countries can offer lessons that can help Sri Lanka fill these gaps with connectivity, technology, and staffing. Peru, for instance, is a large coffee and cocoa exporter under the EUDR and has experienced similar issues. It has established a Registry of Agricultural Producers that assigns farmers a digital identity number linked to the geolocation of their farm. Farmers utilise an offline-enabled mobile app to map their plots and later sync data when internet access is available. This approach enables even remote producers to meet traceability at minimal cost. For Sri Lanka, a step-by-step process may start with digitising high-risk products and areas, then moving to digital IDs for producers, integrating land registry information, and establishing a central compliance certification scheme monitored by a government agency.

Policy Priorities for Readiness

Sri Lanka can accelerate the current mapping and documenting process for the EUDR-covered products by expanding rural internet connectivity and using offline mapping tools where necessary. Digitised land registries linked to producer IDs will be essential for establishing legal ownership. Producer cooperatives will enable smallholders to benefit from economies of scale, reduce compliance costs, and access shared technology. Training farmers on digital tools would streamline these processes and could be a step towards improving the country’s own sustainable agriculture practices.

[1] Based on Wijesinghe, A. and R. Anupama. 2025. Sri Lanka State of the Economy 2025, (forthcoming).

By Dr Asanka Wijesinghe, Chaya Dissanayake, and Rashmi Anupama

Video Story