June, 25, 2025

By Dr. Pulasthi Amarasinghe

In April this year, the Cabinet approved the expansion and extension of Aswesuma. This is timely, as strengthening social protection remains a critical priority as Sri Lanka continues to grapple with the aftermath of its economic crisis. However, Aswesuma’s effectiveness, especially in terms of its impact on household welfare, will depend on its ability to identify the beneficiaries.

The recent publication by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS), Estimating Aswesuma Effectiveness, examines the impact of Aswesuma on targeting welfare improvements for the most vulnerable households. The findings suggests that while targeting the poor is an improvement under the social registry, it can be further developed to improve key welfare outcomes, particularly food insecurity and labour force participation.

The study findings were presented at a roundtable held at the IPS recently, where policymakers and stakeholders discussed the performance of Aswesuma and proposed ways to improve the system's responsiveness. The roundtable highlighted both the achievements of the programme and emerging challenges, such as the difficulty of capturing transient poverty and the importance of refining the eligibility criteria.

Current Transfers: Simulated Impacts on Household Welfare

The Aswesuma programme uses the newly developed digitised social registry to identify and distribute benefits. The social registry aims to modernise social protection toward a long-term, transparent, flexible, data-driven social registry aimed at better identifying and supporting households in multidimensional poverty. At the inception of the programme, the Aswesuma scheme provided tiered cash transfers ranging from LKR 2,500 to LKR 15,000 based on households' poverty levels.

The targeting mechanism used for Aswesuma, launched in the wake of the economic crisis, represented a structural shift, moving from income-based to multidimensional poverty targeting using a social registry. Using 22 indicators across the six dimensions of education, health, housing, assets, demographics, and economic status, the programme promised a more holistic and objective framework to reach the most vulnerable communities by looking at the weighted deprivation of households across the 22 criteria. With Cabinet-approved amendments in April 2025 (awaiting Parliamentary confirmation), households are expected to receive cash transfers ranging from LKR 5,000 to LKR 17,500. The IPS study shows that these eligibility criteria are an improvement over Samurdhi eligibility, targeting households that are more vulnerable across key poverty indicators. Given the improvement, the study focuses on the impact of outcomes and alternative criteria to enhance the benefits of cash transfers (details of the comparison are provided in the report).

In addition, the IPS study showed mixed results on two welfare outcomes, namely labour force participation and food security. Results show that with the new Aswesuma, food insecurity decreased, but it also negatively affected the labour force participation, with a much greater reduction in labour force participation seen for males.

Figure 1: Simulated Effects of Food Insecurity Experience and Labour Market Participation Under Current and Proposed Aswesuma Payment Schemes

Source: Author’s Estimations using HIES 2019.

Initial Aswesuma transfers reduced food insecurity for recipient households by an average of 2.6 percentage points, with a 7.1-point drop among the “severely poor.” With the new amendments, these reductions are projected to rise to 3.4 points on average and a striking 11.2 points for the most deprived households.

However, the gains in food security come with a trade-off. Labour force participation, especially among men, is expected to decline more sharply with the revised benefits. As economic theory predicts, non-labour income can reduce incentives to engage in paid work, particularly in informal sectors where wages are low and opportunity costs are minimal.

Male labour force participation is projected to fall by 5.4 percentage points under the revised scheme (up from 4.2 points under the original). For women, the reduction is more minor, at 1.3 percentage points. These trends highlight the importance of combining cash transfers with activation policies to promote employment, skills development, and labour market reintegration.

Can Targeting Be Improved?

A key topic raised during the roundtable was the need to improve how households are identified. Simulations in the IPS study explore whether alternate selection criteria could better capture at-risk populations while preserving programme efficiency.

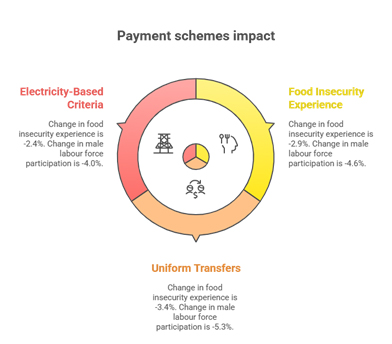

Figure 2: Simulated Effects of Food Insecurity Experience and Labour Force Participation Under Alternative Selection Criteria and Payment Schemes

Source: Author’s Estimations using HIES 2019.

First, when exposure to climate-related disasters is included as an additional eligibility factor, food insecurity decreases by 2.9 percentage points across the board, with even sharper declines for the poorest populations. This highlights the vulnerability of disaster-prone households, which may not be categorised as poor based on conventional assets or income indicators but remain at a high risk. Including such dynamic risks in the eligibility algorithm could make Aswesuma more responsive to future shocks.

Second, providing a flat LKR 15,000 to all eligible households results in a 3.4 percentage point drop in food insecurity, the most substantial improvement among all scenarios. However, this approach is significantly more expensive and leads to a greater fall in male labour force participation, raising concerns about long-term fiscal sustainability and disincentives to work.

Third, using single indicators, such as electricity, has been widely suggested in public discussions regarding Aswesuma. Simulations suggest that an alternative eligibility model based solely on electricity consumption performs less effectively than the current 22-indicator model in identifying households that are vulnerable. Despite its simplicity and administrative ease, a criterion based solely on electricity consumption risks overlooking hidden forms of deprivation, especially in rural or peri-urban settings, where non-monetary poverty is more complex and nuanced.

Looking Forward: Lessons from the Roundtable

The discussion at IPS provided several policy lessons that extend beyond simulations, improving local-level data verification, especially for disaster and climate exposure, refining multidimensional indicators to include transient poverty and nutritional risks, and monitoring socio-economic outcomes to track progress toward poverty “graduation.”

As Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne, President of the Sarvodaya Movement, noted during the discussion, the programme was fast-tracked to meet urgent needs, but the underlying targeting system and registry require careful review. Mr. Rajapakse, Additional Commissioner at Welfare Benefit Board, also emphasised plans to consolidate welfare schemes and invest in stronger data systems through development officers on the ground.

The revised cash transfer based on an integrated social registry represents a major step forward in reducing food insecurity and supporting vulnerable households. As such, the roundtable highlighted the foundations of the current social protection landscape as a success in a move towards a more transparent and well-targeted system.

However, long-term success will depend on how well Sri Lanka can balance short-term relief with efforts to promote labour force participation, reduce dependency, and support individuals in graduating from poverty. Thus, to build resilience, social protection must become more adaptive and responsive not only to deprivation but also to the dynamic risks that shape household vulnerability in Sri Lanka today.

Dr. Pulasthi Amarasinghe

You can find our latest report Estimating Aswesuma Effectiveness here.

Video Story