February, 9, 2026

Worker remittances to Sri Lanka have set a new all-time high record with USD 8.076 billion in 2025. This 22.8% growth, compared to the USD 6.6 billion received in 2024, is shaped by the high number of worker departures experienced in recent years.

While migrant workers’ contribution to easing pressure on the country’s balance of payments is widely appreciated, the hardships and sacrifices they endure are often overlooked. This blog highlights the challenges faced by migrant workers, drawing evidence from two recent studies by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS).

Migrant Destinations and Remittance Origins

The composition of the largest remittance-sending countries corresponds with the main destinations of Sri Lankan migrant workers. In 2025, the top destination for Sri Lankan migrant workers continued to be the Middle Eastern region, with Kuwait ranked first, followed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia.

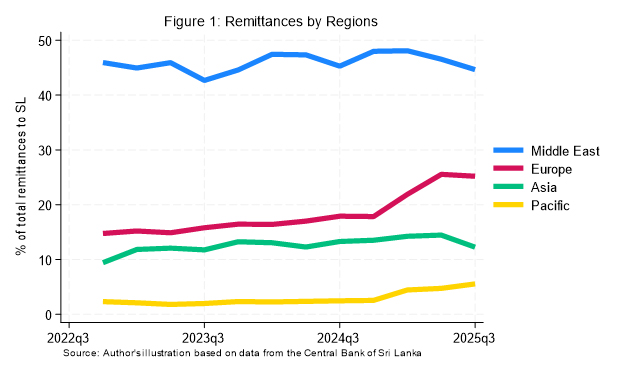

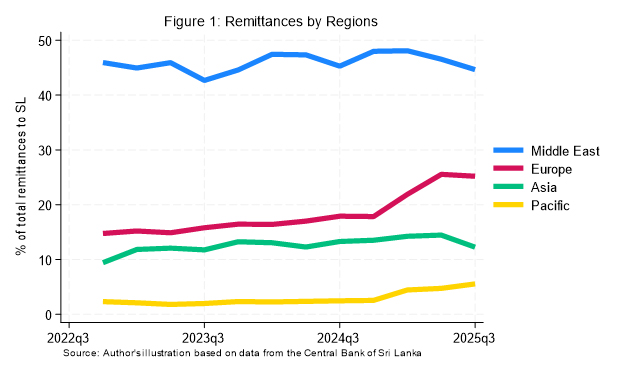

Similarly, the largest share of remittances to Sri Lanka is sent by migrant workers in the Middle Eastern region. Available data for the first three quarters of 2025 indicate that the highest share of remittances were sent from Kuwait (10.7%), UAE (10.4%) and Saudi Arabia (9.4%). Yet the share of remittances from these countries has either stagnated or declined in recent quarters (see Figure 1), while countries that attract more skilled and long-term migrants have increased their contribution to remittances to Sri Lanka (Figure 1). For instance, remittances from countries such as France, Canada, and Australia have doubled their shares between the fourth quarter of 2022 and third quarter of 2025, while shares from Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman have declined in the same period.

As such, one key reason for growth in remittances could be the increase in departures of higher skilled workers in recent years, and their related capacity to remit more with their higher incomes. Other possible reasons include an increase in formal remittances driven by a reduced gap in official and unofficial foreign exchange rates, and an increased confidence in the financial system and the overall economy due to the post-crisis recovery process.

Impact on Families Left Behind

Despite the higher inflows and the undoubted positive impacts of migration and remittance earnings, families left behind make immense sacrifices in coping with the realities of migration. A study to which the IPS contributed highlights the trade-offs between the economic opportunities provided by international migration and the benefits of a mother’s presence for child development.

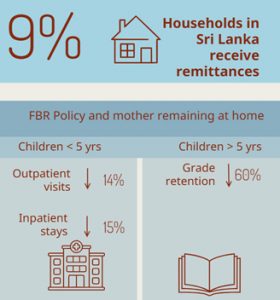

Although around 9% of households in Sri Lanka receive remittances from abroad, this study, based on data from three waves (2009/10, 2012/13 and 2016) of the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) finds that the mothers’ presence at home, arising from the Family Background Report (FBR) restriction, contributes to better health and educational outcomes for children. Adherence to this restrictive migration policy reduces outpatient visits for illness among children under 5 years of age by 14% and inpatient stays by 15.2%, relative to similar children whose mothers are not at home.

A possible counterargument is that restricting mothers’ foreign employment—and the resulting decline in overseas remittances—could reduce access to healthcare services, without any real change in the children’s underlying health status. However, the analysis shows that when the FBR restriction lowers remittances from abroad, this is offset by a corresponding increase in domestic remittances, leaving overall household income largely unchanged. Moreover, healthcare in Sri Lanka is largely free. Together this means it is more likely that the improvement in child health comes from the mothers’ presence at home.

This study also shows that among older children, a mother’s presence at home has a causal effect in reducing students from failing/repeating a grade (grade retention) by 60% when compared to a control group. Therefore, women’s migration for foreign employment and related remittances has a trade-off with their children’s health and education-related human capital development outcomes.

Abuse and Exploitation Abroad

Amidst multiple positive implications associated with migration, including improved income, skills development, human capital accumulation, enhanced career mobility, and increased empowerment, migrant workers also make considerable sacrifices and, at times, endure hardship while working abroad. These sacrifices include family separation and, on occasion, debt, financial pressure, limited rights, reduced autonomy, and exposure to exploitation and abuse. One reason for the introduction of the FBR policy was to safeguard female workers against the exposure to exploitation and abuse in the countries of destination.

An IPS study also shows that 7,448 complaints were made in 2024 by migrant workers (equivalent to 2% of departure in same year). Of these, 41% were reported from Saudi Arabia, 34% from Kuwait, and 10% from the UAE. Of all complaints, a majority (76%) were made by female domestic workers originating from Middle Eastern countries.

The study suggests that many Sri Lankan female domestic workers migrate due to dire financial conditions, including high household debt, lack of employment opportunities, and the need to support dependents, which makes them economically dependent on remittances. While underscoring that NOT all female domestic workers experience hardship or sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), among those who do experience such issues, “this economic dependency increases their vulnerability to abuse”. This is mainly because of delays in or avoidance of reporting abuse due to fear of job loss, related income decline, and their inability to remit earnings.

As such, in “this heightened level of acquired tolerance, female domestic workers often delay seeking support”. For instance, some migrant workers continued their employment despite abuse and non-payment of wages, in the hope of accessing their accumulated wages. Similarly, many were compelled to take up the sub‑optimal choice of changing employers even when their preferred solution was repatriation. In some cases, financial challenges associated with losing the employment opportunity and difficulties in affording repatriation forced them to return to the same employer instead.

Policy Recommendations

As such, while acknowledging the record high remittances sent by migrant workers, it is also important to understand the sacrifices and hardship endured by them and their families and minimise these negative impacts. A key policy recommendation emerging from both these recent studies is to safeguard the rights of female workers. Towards this, it is important to transition from a reactive support structure to a preemptive one. The current support mainly involves warning or changing employers and repatriation of workers after facing and reporting SGBV. A pre-emptive support structure can help identify risk for vulnerability early and provide support to prevent exposure to SGBV. For example, contacting a migrant worker within the first month of employment to assess working and living conditions can help identify the extent to which actual conditions align with the formal employment contract, thereby minimising future issues.

This procedure could be implemented once or routinely, through a telephone interview conducted by an official at the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment, the Sri Lankan Embassy, or via a social media survey. Such enhanced safeguarding of female workers’ rights would minimise the trade-offs between the benefits of migration and remittances, and the hardships and sacrifices experienced by migrant workers and their families.

Research Fellow and Head of Migration and Urbanisation Policy Research,

Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS)

Video Story