November, 9, 2023

By Manisha Weeraddana

In a small roadside hut in Nattandiya, Asoka Malini, a returnee migrant worker, spends her days with a handful of vegetables. She worked for 6 years in Saudi Arabia as a housemaid and a care worker, earning a monthly salary of LKR 20,000. As a mother of two, Asoka now faces an uncertain future after returning from her stint abroad.

With the recent launch of the National Policy and Action Plan on Migration for Employment (2023-2027), it is timely to draw up a picture of Sri Lankan returnee female migrant workers like Asoka and the socio-economic nuances that determine the ultimate decision-making of these women to migrate and/or reintegrate. This blog sheds light on the hidden struggles of such returnee female migrant workers to identify areas for potential policy actions, especially regarding economic reintegration, drawing on a recent IPS study investigating the skills, aspirations, and reintegration challenges of return migrant workers.

A majority of Sri Lankan females migrate in search of a source of income that would, at the least, help them get rid of debt burdens and ease financial difficulties back home. Thus, they expect to return home as soon as their financial targets are met. However, the decision to return home takes place with close to zero plans regarding their long-term economic sustainability. In fact, these migrant workers rarely see the need for such reintegration as they do not understand the economic and labour market realities until they try to reassimilate into their lives back home.

Key Concerns:

The IPS study opened up interesting insights into the lives of Sri Lanka’s return female migrant workers. The study collected data from 511 return migrant workers randomly selected from Kandy, Kurunegala, Puttalam, Anuradhapura and Vavuniya.

“Here there is no specific work nearby. Sometimes, there is work in vegetable fields … we get around LKR 1000-1200. But it is very hard to find work”.

Asoka points out a major issue faced by return female migrant workers in the sample. A good part of those who stated lack of job opportunities as a major impediment faced during economic reintegration are considering re-migration or settling down to opening small boutiques with whatever they have managed to save up from their time abroad. Thus, in a way, the decision between successful reintegration and remigration mostly deals with the lack of job opportunities in rural areas.

“Can’t leave my daughter and go in search of jobs… Earlier his (husband’s) mother was there ...” says Asoka.

Sri Lankan women who migrate for work seem to act on borrowed time which allows them to migrate, earn, send home their incomes, and return home when “time runs out” or in other words, when the support system back home can no longer accommodate the household duties left vacant by a woman. Asoka’s voice, echoing a prominent theme in Sri Lanka’s female economic participation, opens a new dimension to the discourse surrounding female migrant workers and their decision and capacity to be economically active.

Economic Empowerment of Returning Female Migrant Workers

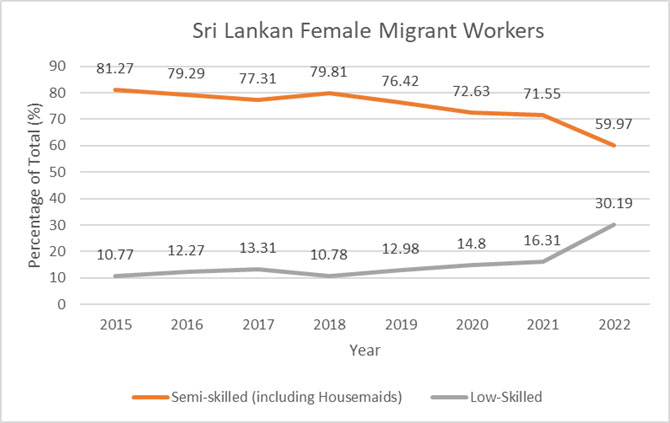

Figure 1: SLBFE Registered Female Migrant Workers by Skill Category

Source: Author’s compilation based on SLBFE 2021 statistics

Even though most return female migrants are categorised as low-skilled or semi-skilled workers, they possess years of experience as caregivers and domestic workers that should ideally have given them a greater capacity to reintegrate into the Sri Lankan economy. However, most return female migrants are hesitant to pursue similar job opportunities within the local context. This hesitancy is fueled by lack of information regarding well-paying job opportunities for domestic workers/caregivers in urban areas, the social stigma associated with domestic work and challenges in finding work closer to home.

The lack of job opportunities in nearby areas highlights another socio-economic dynamic within households of return migrant women, i.e., support systems that make working away from home a possibility. What is peculiar about these systems is that, for some women, they only exist for a limited period of time. For others, a support system appears to be created, even a second time around, in the face of potential income generation specifically if it happens to be in the familiar realm of migrant work.

These subtle nuances of the economic reintegration of female returnee migrants beg policy interventions as well as further research regarding the matter. The 2023-2027 National Policy plan does cater to some of the issues presented. For instance, Core Policy 3 focuses on the promotion of employment opportunities for skilled and semi-skilled migrant workers which can in turn expand the migrant workers’ chances of economic reintegration and financial security. Strategy 4.3.4 under Core Policy 4 focuses on entrepreneurial support for female return migrant workers which can improve the economic reintegration of those who cannot move too far from home in search of job opportunities.

Nonetheless, further measures are needed, starting with creating awareness surrounding the potential work opportunities for domestic workers within Sri Lanka, and the creation of links between the existing market for care work and the potential labour in rural areas in order to make job opportunities in the area of care work more accessible for those who have already finished their migration process and will not be able to upskill any further or those who do not feel inclined towards entrepreneurship. This can provide women who are forced to remigrate as domestics, especially through familial connections, a chance to consider opportunities within a more familiar and safer setting. Furthermore, additional research on socio-cultural dynamics within communities where female outmigration is prevalent is needed to provide context-sensitive policy actions.

Video Story