November, 12, 2024

Sri Lanka’s foreign-exchange reserves surged by an impressive 81% year-on-year in October 2024, reaching USD6.5 billion due to the support of its IMF program, according to Fitch Ratings. This boost in reserves is a significant development for the country's economic stability, providing a stronger buffer against external shocks. However, Fitch notes that Sri Lanka’s improved financial position could face a setback if the government resumes servicing its external debt, as the island nation’s credit rating remains in 'Restricted Default' (RD) status.

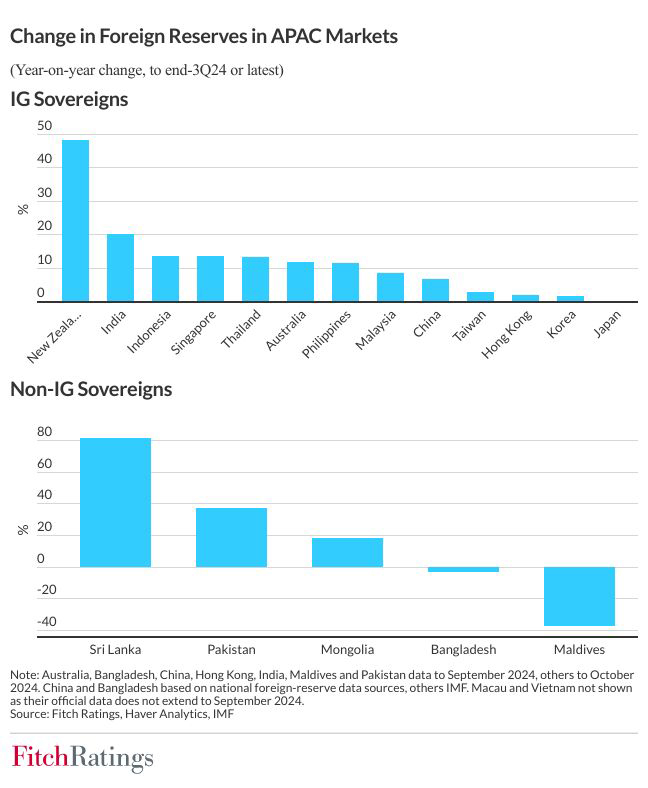

Fitch Ratings-Hong Kong-11 November 2024: Foreign-exchange reserves are rising across the vast majority of rated Asia-Pacific (APAC) sovereigns in Fitch Ratings’ portfolio and, if sustained, will strengthen external buffers and support the credit profiles of many sovereigns across the region, says Fitch. However, rising reserves could also contribute to international tensions over exchange-rate policies in some cases, while in others, US dollar strength could lead to rising foreign-exchange interventions and a fall in reserves.

We estimate that reserves rose during 3Q24 in at least 15 of the 20 APAC sovereigns in Fitch’s portfolio. This continues the trend over the last 12 months, in which at least 10 have seen double-digit percentage increases. Higher reserves are unlikely to affect the credit profiles of highly-rated sovereigns such as Singapore (AAA/Stable) and New Zealand (AA+/Stable), but rising reserves would be modestly positive for the capacity of some large emerging markets to respond to shocks, such as Indonesia (BBB/Stable) and the Philippines (BBB/Stable).

Improved external buffers would have an especially positive effect on credit profiles of APAC’s frontier markets, which are also more vulnerable to a strong US dollar from rising protectionism. Pakistan’s gross foreign-exchange reserves reached USD17.4 billion at end-September, up from a trough of USD7.9 billion in January 2023. When we upgraded Pakistan’s rating to ‘CCC+’ in July, we stated that improved foreign-exchange levels and further fiscal consolidation were likely in light of the greater external funding certainty from its recently agreed USD7 billion Extended Fund Facility with the IMF. However, Pakistan's large funding needs would leave it vulnerable if its access to external finances were constrained, for example due to a failure to implement the challenging reforms under its IMF programme.

The Maldives was one of the few APAC sovereigns whose foreign reserves fell in 3Q24, by 27% qoq to USD371 million, only USD49 million net of short-term liabilities. Our decision to downgrade the Maldives to ‘CC’, from ‘CCC+’, in August 2024 was driven by our assessment that intensified external liquidity pressures had made default more likely.

The Indian government’s announcement on 7 October that it would provide currency swap agreements to the Maldives, worth around USD757 million in total, should provide near-term relief. Nevertheless, external liquidity strains will most likely remain high in the next two years without radical policy adjustments, with total debt servicing requirements of USD557 million in 2025 and over USD1.0 billion in 2026. The swaps will have to be repaid and do not resolve the underlying issues of high and rising public debt in combination with low foreign reserves and a hard peg to the US dollar.

Sri Lanka’s gross official reserves soared by 81% yoy to USD6.5 billion in October on the back of the IMF programme, but the speed of the recovery in reserves is likely to be set back if the government resumes servicing its external debt. Its improved external buffers will only begin to influence the sovereign’s rating once it moves out of ‘RD’.

The broad upward trend in APAC foreign reserves is generally credit positive for the region’s sovereigns and may help cushion the impact of any fallout from rising trade tensions. However, it could also increase geostrategic tensions – particularly with the US – if it is perceived as a sign that governments are maintaining weaker currencies to strengthen their trade competitiveness. US president-elect Donald Trump previously said the US has a currency problem and suggested that weak currencies give some countries an unfair competitive advantage when it comes to trade.

Video Story