January, 30, 2026

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) accounting for nearly 75% of all deaths, have emerged as a major health challenge in Sri Lanka over the past few decades. Unhealthy dietary patterns – including excessive intake of sugar, salt, and fats – continue to play a significant role in this escalating issue. To curb excessive sugar consumption, Sri Lanka introduced a Traffic Light Labelling (TLL) system indicating high (red), medium (amber), and low (green) sugar levels, alongside a sugar-based excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). However, as manufacturers reformulate beverages to meet sugar thresholds, a new issue has emerged – the rapid rise of non-sugar sweeteners (NSS) in “low sugar” products. This blog discusses how Sri Lanka can strengthen its SSB policies to respond to this evolving challenge.

The Rise of NSS in “Low Sugar” Drinks

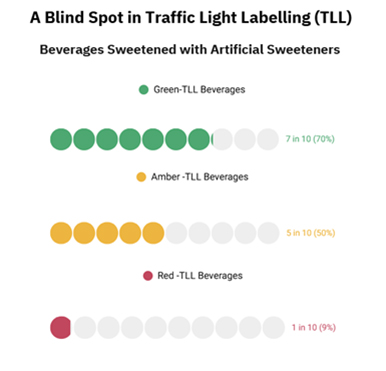

A recent IPS assessment of SSB labelling reveals that around 70% of green-labelled SSBs and 50% of amber-labelled ones contain NSS. While these reformulations help products meet sugar thresholds, they contain artificial sweeteners and may pose long-term health risks.

Based on evidence from a systematic review, the World Health Organization (WHO) warns that long-term NSS consumption is linked to a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and mortality among adults. Moreover, the review indicates that a higher intake of NSS is linked to increased body weight, a greater risk of obesity, and higher risks of diabetes, heart disease, and death from all causes. The WHO also stresses that NSS should not be used for weight control or NCD prevention, except for individuals with diabetes who require sugar alternatives. Reformulation using artificial sweeteners should not replace genuine efforts to lower free sugar consumption.

Coverage of NSS under Sri Lanka’s Current SSB Policy Landscape

Sri Lanka’s current SSB policies—TLL and SSB taxation—do not cover or regulate the use of NSS. This allows manufacturers to reduce sugar levels to meet policy thresholds while continuing to market products sweetened with artificial sweetners. Under the existing Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) system for SSBs, TLL criteria is based only on sugar content, meaning products containing NSS often receive green or amber labels, which can mislead consumers into viewing them as healthier choices. Similarly, artificial sweeteners are excluded from the SSB tax, creating an incentive for manufacturers to shift from sugar to NSS. These gaps highlight the need to update and strengthen SSB control policies to address all forms of sweeteners comprehensively.

What the World Is Doing: Lessons from Global Best Practices

Nutrient Profile Model

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Nutrient Profile (NP) model guides governments to regulate products more comprehensively, preventing loopholes created by reformulation. The PAHO NP model considers any amount of other sweeteners as part of an unhealthy food profile.

FOPL and Sweetener Warnings

Countries such as Mexico, Peru, and Argentina have introduced two types of FOPL warning labels. Mexico’s FOPL is the strongest in flagging unhealthy foods. Based on the PAHO NP model, Mexico introduced a mandatory FOPL system in 2020 that flags products high in energy, sugar, saturated fat, trans fat, sodium, non-nutritive sweeteners, and caffeine. The system uses five black warning octagons to indicate excessive calories, sugar, sodium, saturated fat, and trans fat, alongside two warning rectangles for the presence of caffeine or non-nutritive sweeteners. This clear and prominent design helps consumers quickly recognise products that may pose health risks.

Inclusion of NSS in SSB Taxes

Countries like Chile, France, India, the Philippines, and Portugal have expanded SSB taxes to include drinks containing artificial sweeteners, not just added sugar. This discourages excessive consumption of both sugary and artificially sweetened beverages. For example, the Philippines applies a volume-based excise tax on SSBs containing sugar and artificial sweeteners, with both sugar and NSS subject to taxation.

The Way Forward

To effectively reduce free sugar intake and promote healthier dietary patterns, national nutrition policies should adopt a comprehensive approach. As recommended in the WHO NSS guidelines, policy actions should prioritise improving the overall quality of diets rather than focusing solely on reducing free sugar consumption.

In conclusion, strengthening Sri Lanka’s SSB fiscal polices and regulatory framework is essential to safeguard public health as the use of NSS continues to rise in response to existing sugar‑focused policies. International evidence shows that comprehensive measures—covering both sugar and artificial sweeteners through fiscal policies, FOPL and sweetener warnings—are more effective than sugar‑only measures. Updating national fiscal policies and regulations to include products containing NSS will help close current policy gaps, reduce consumer misperceptions, and encourage healthier reformulation. By adopting a holistic, evidence‑based approach, Sri Lanka can advance its nutrition agenda and better address the growing burden of diet‑related NCDs.

Video Story