November, 6, 2024

By Dr Bilesha Weeraratne

The recent presidential election in Sri Lanka marked a series of "firsts," setting it apart from previous elections. It saw a record-low number of 350,516 valid voters per candidate, implementation of the Regulation of Election Expenditure Act of 2023, and a second count of votes. Notably, there was also greater engagement from Overseas Sri Lankans (OSLs) in the country’s electoral process than at any time previously.

Indeed President Anura Kumara Dissanayaka actively engaged with Sri Lankan expatriates during his campaign, visiting countries including South Korea, Australia, the USA, Canada, Sweden, the UK and Japan. Continuing a trend from the previous presidential election in 2019, there was evidence of Sri Lankans returning to vote. However, despite this enthusiasm, the long-standing debate over granting OSLs the right to vote from abroad remains unresolved. Of the OSLs, it also means 1.5 million Sri Lankan workers abroad could not vote in the recent election according to the SLBFE.

Voting with Their Wallets

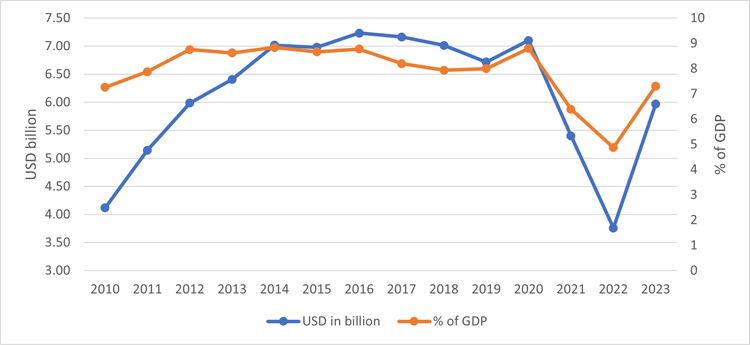

While OSLs may not have voting rights yet, those who regularly remit earnings back to Sri Lanka have already demonstrated their influence—by voting with their wallets. In the run-up to the 2022 economic crisis, government efforts to attract more formal remittances by offering higher interest rates failed to convince OSLs, as the formal foreign exchange rate offered was far below the informal rate. As a result, in 2022, remittances to Sri Lanka declined by a record 42%. Compared to the steady 10-year average USD 6.4 billion inflow (from 2010 to 2020), the decline to USD 3.7 billion was the final nail in the coffin that sparked the 2022 sovereign debt default.

Figure 1: Annual remittances in USD Billion and as a Percentage of GDP: 2010-2023

Source: CBSL

Remittance and Voting Rights

The literature identifies three mechanisms for linking the receipt of remittances with political participation.

1) Income Channel: those with greater resources are able to devote more resources (both in terms of material support and time) to political activities;

2) Independence Channel: remittances reduce the dependence of recipients on the government for material prosperity; and

3) Insurance Channel -remittances promote feelings of economic security in recipients that allow them to pay more attention to non-material concerns.

While these mechanisms are for all voters in households receiving remittances, OSLs prefer a say in how the macroeconomy back in Sri Lanka is managed by elected officials, i.e. how does the government spend the foreign exchange OSLs regularly send as remittances? what are the interest rates on their savings? how is inflation feeding into the purchasing power of their remittances? how is the foreign exchange rate affecting the disposable income of their remittances? how are savings and investments of their remittances taxed? and what are the public services available to their families left behind? to name a few. The answers to such questions are linked to election promises and how governments actually perform when in office. Voting rights would allow OSLs a voice in economic policies that impact their remittances and financial interests in Sri Lanka.

Overseas Absentee Voting: A Long-Awaited Promise

Providing voting rights or Overseas Absentee Voting (OAV) has been in discussion for many years, with various candidates, including the current president, promising to make it a reality. Sri Lanka has also ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, which calls for migrant workers’ voting rights (Article 41). Many previous governments, though keen, have not been successful on this front. Previous efforts include a Parliamentary Select Committee for Electoral Reforms recommending voting rights for OSLs in 2021, and a Special Presidential Commission in 2023 (among other issues) being required to make recommendations on a mechanism for OSL voting rights. In 2023, the Election Commission developed a beta version of an online method for registering OSLs for voting. However, according to the Commissioner General of Elections their hands are tied “until the Parliament passes a law to enable migrant workers to vote from their destination states.”

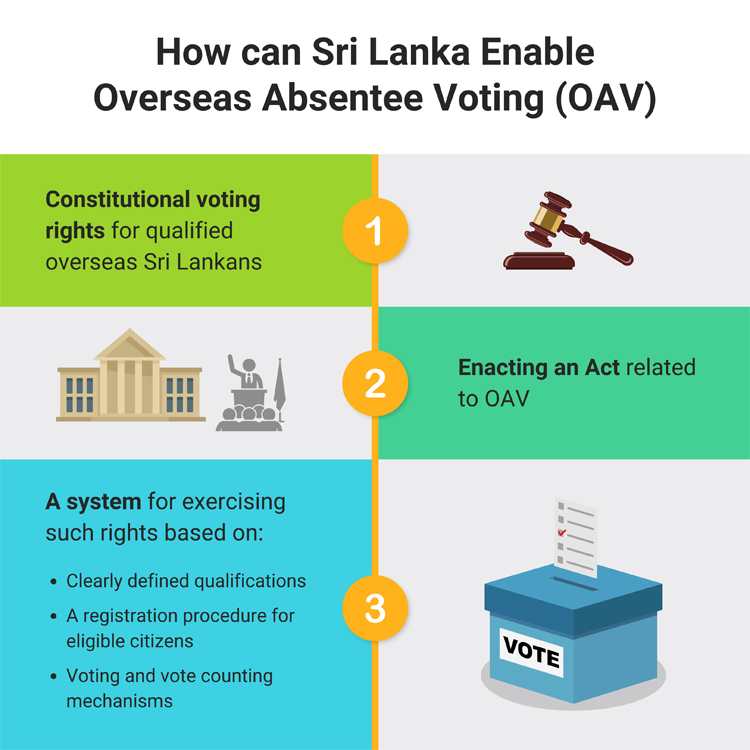

How to Make Overseas Absentee Voting a Reality

There are many possible and sophisticated ways to implement OAV, including advanced in-person (similar to postal voting in Sri Lanka), voting by mail, facsimile, or internet, as well as proxy voting (where a duly authorised representative or a proxy vote on behalf of the absent voter). Some countries such as the Philippines, for instance, use a combination of in-person and postal voting.

For Sri Lanka, keeping things simple would be one important mindset in transitioning from an eternal election promise to making overseas absentee voting a reality. A manageable starting point could be advanced in-person in-embassy voting, which would function analogous to Sri Lanka’s postal voting system. Embassies could serve as analogous to postal voting centers for expatriates, and OLSs to postal voters.

Hence, learning from the Philippines, a few key steps in the process of allowing in-person in-embassy voting are:

Not an Easy Road

Implementing OAV will not be without challenges. For Sri Lankans residing in countries without a local embassy, registration and voting might require travel to the nearest consular post. While critics would highlight that time and financial cost would “deter the diaspora from proactively partaking in voting”, employees such as female domestic workers would have the added challenge of seeking “approval of their masters and traveling a long distance to both register and vote”. Mail voting or assigning longer voting periods, including weekends, could alleviate some of these concerns.

Other concerns of out-of-country voting include potential vote buying and exploitation. Activists also raise concerns about whether politically appointed staff in diplomatic missions would influence, especially the unskilled and voiceless OSLs. Therefore, there is a need for a “mechanism with checks and balances” to “prevent the integrity of the electoral result from being questioned”.

While criticisms of each optional OAV method will likely emerge, it is important to start taking initial steps toward one feasible and practical option. The issues can be ironed out with time, and more sophisticated options can be pursued.

Finally, it is important to realise that achieving this goal in time for the upcoming Parliamentary election on 14 November or the pending provincial or local government elections in 2025 is not easy. Yet, initial steps towards this change are much needed and the time is right for it.

Dr Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow and Head of Migration and Urbanisation Research at IPS. Prior to re-joining IPS in 2014, she was a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Princeton University, New Jersey, USA. Her research interests include internal and international migration, climate mobility, urbanisation, the economics of education, labour economics, economic development, econometrics and economic modeling. She holds an MA in Economics from Rutgers University, USA and an MPhil and PhD in Economics from the City University of New York, USA.

Video Story