April, 30, 2020

Moody’s Investors Service yesterday (29) warned that Sri Lanka is facing simultaneous domestic and external shocks amid the global coronavirus outbreak.

The rating agency in its latest report stated that the country faces multiple challenges from capital outflows, marked local currency depreciation, wider risk premia and a further decline in real GDP growth that will raise Sri Lanka’s debt burden, liquidity constraints and the cost of external debt servicing.

“This comes at a time when Sri Lanka’s credit profile is highly vulnerable given low reserve coverage of large forthcoming external debt service payments and very weak debt affordability,” the report said.

The rating agency has already placed Sri Lanka currently holding a B2 sovereign rating for a review, which will likely result in a downgrade.

Full report as follows;

Government of Sri Lanka

Global coronavirus outbreak exacerbates government liquidity and external risks

Sri Lanka (B2 review for downgrade) is facing simultaneous domestic and external shocks amid the global coronavirus outbreak. Capital outflows, marked local currency depreciation, wider risk premia and a further decline in real GDP growth will raise Sri Lanka's debt burden, liquidity constraints and the cost of external debt servicing. This comes at a time when Sri Lanka’s credit profile is highly vulnerable given low reserve coverage of large forthcoming external debt service payments and very weak debt affordability.

» Acute tightening in global financing conditions compounds weaker near-term growth, fragile fiscal and external positions Higher financing costs, wider deficits and a steeper trajectory for Sri Lanka's debt burden will weaken the government's already fragile fiscal position. The government has sought multilateral and bilateral external financing which will help to cover imminent repayments. However, the government’s external debt service payments amount to around $4 billion annually over 2020-25, on top of wider budget deficits, which will be partially funded externally. We expect that the government will increasingly tap domestic financing sources; however, refinancing external debt domestically would further weaken the rupee and already thin foreign exchange reserve adequacy. We expect the fiscal deficit to increase to over 8% of GDP over the coming years, on weaker government revenue and greater spending. Given wider fiscal deficits, we expect Sri Lanka's debt burden to rise to nearly 100% of GDP, weakening Sri Lanka's already fragile fiscal position.

» Limited policy flexibility and effectiveness accentuate risks, while dimming prospects for addressing macroeconomic imbalances Amid the currently turbulent environment, we expect that Sri Lanka will face difficulties in managing the country's twin deficits. An elevated debt burden and rigid budget structure constrain fiscal policy space. Meanwhile, a trade-off between anchoring inflation expectations and supporting growth, and a potential rise in borrowing costs, will constrain monetary policy effectiveness. The lack of an effective and credible policy response to arrest a more severe and prolonged deterioration in credit metrics would further dim prospects for reforms that would meaningfully strengthen Sri Lanka’s fiscal and external positions. The delay in general elections could add to this challenge.

Higher financing costs, wider deficits and a steeper trajectory for Sri Lanka's debt burden will weaken the government's already fragile fiscal position. Since the outset of the global coronavirus outbreak and weaker global economic outlook, large capital outflows and increased pressure on the exchange rate have tightened financial conditions.

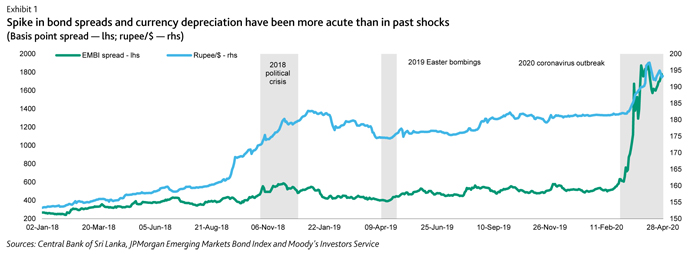

The Sri Lankan rupee has depreciated by around 6% against the dollar since the beginning of March 2020. Concurrently, spreads on Sri Lankan international sovereign bonds over US Treasuries have widened sharply in recent weeks to around 1600 basis points, indicating significantly impaired market access (see Exhibit 1).

These conditions are raising Sri Lanka’s cost of servicing external debt, weighing on foreign exchange reserves and jeopardizing macroeconomic stability.

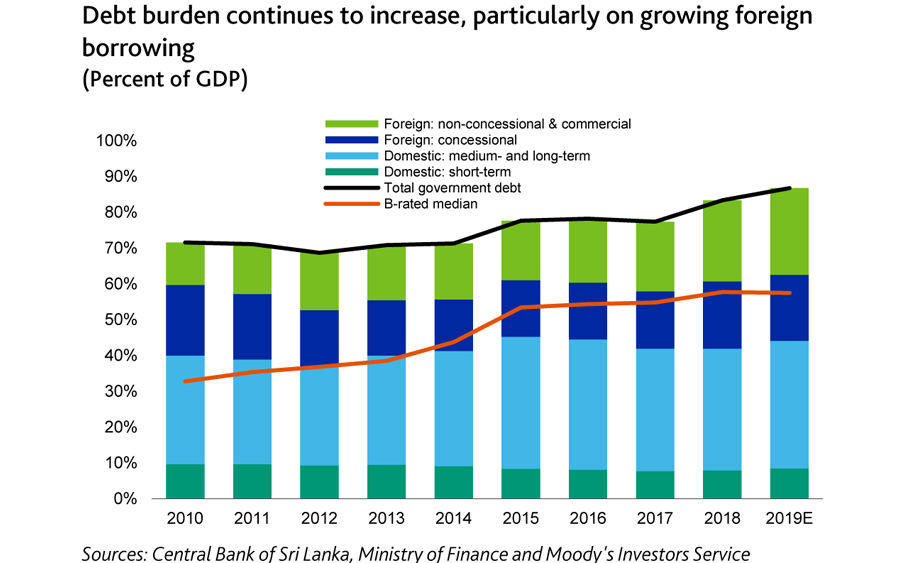

External and foreign currency-denominated debt accounted for about one-half of total government debt as of 2019. As such, a prolonged tightening in external financing conditions would add significantly to the government’s debt burden and debt servicing costs.

Weaker near-term growth outlook raises existing credit challenges

An islandwide curfew and lockdowns in major manufacturing and services activities in some regions of the country since 20 March will slow the domestic economy through weaker consumption and investment.

Particularly for the informal sector, which employs a substantial portion of the population, weak economic activity will hurt households' incomes and purchasing power. We expect construction activity, which grew just 1.7% year-on-year in the fourth quarter, to take a major hit amid supply-chain disruption.

A sharp drop in tourism activity will hurt external demand which, at around 5% of GDP, had not entirely recovered from the 2019 terrorist attacks. Moreover, weaker demand for Sri Lankan textile and garments from North America and Europe will weigh on export volumes. Together, these two regions account for around two-thirds of Sri Lanka's total exports.

Given global travel and activity restrictions and weaker oil prices, we expect to see a decline in overseas remittances of around $1.5 billion (about 2% of 2020 forecast GDP). This will weigh on foreign exchange inflows and domestic consumption.

Despite the weaker foreign exchange inflows, we expect the current account deficit to narrow on the lower import oil bill and significant import compression.

We expect economic growth to slow to 1.5% in 2020, with risks tilted sharply to the downside. If greater community transmission leads to stricter and more prolonged domestic activity restrictions and further dislocation throughout the Sri Lankan economy, this would dim prospects for a second half recovery.

Refinancing needs are large and growing, with rising uncertainty over sources

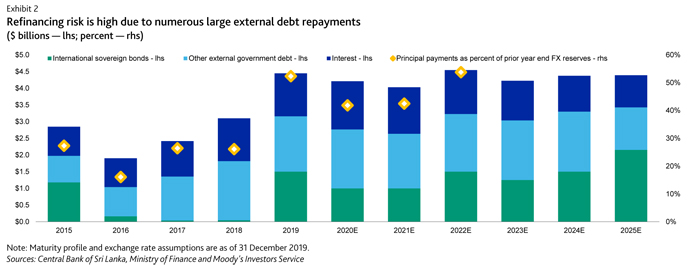

Sri Lanka's gross external financing needs are large, mostly reflecting maturing government debt repayments (sovereign bonds, bilateral and multilateral loans, and concessional debt).

The government's external debt servicing payments will be around $4.0 billion to $4.5 billion annually over 2020-25, or around $25.8 billion in total. This amount includes international sovereign bonds of $1.0 billion each in October 2020 and July 2021. It does not account for any further external financing of the budget deficit in coming years. Dollar international sovereign bonds account for $8.4 billion, or about 30%, of all maturing external government debt service payments over 2020-25 (see Exhibit 2).

At these levels, Sri Lanka's bond maturities are among the highest of rated frontier market sovereigns as a proportion of foreign

exchange reserves. The low reserve levels highlight the government's significant exposure to refinancing risk. The government has sought multilateral and bilateral sources for external financing that will help to cover imminent repayments. We expect that the authorities will increasingly tap domestic financing, particularly given our expectation for wider fiscal deficits in the coming years.

However, refinancing external debt domestically would dent reserves further, weakening foreign exchange reserve adequacy, which is already thin, and potentially resulting in greater local currency depreciation. Moreover, domestic debt has come at higher cost and shorter maturities than external debt, particularly when contracted on more concessional terms.

The government has taken measures to secure financing from nonmarket sources, including securing both lending and swap facilities. In March 2020, Sri Lanka secured a $500 million syndicated loan from China Development Bank (A1 stable), which we expect to increase to around $1.2 billion in the current year. The government has also requested around $800 million over the next two years from the IMF under the Rapid Financing Facility, as well as seeking additional funding from the Asian Development Bank (ADB, Aaa stable), the World Bank (IBRD, Aaa stable), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, Aaa stable) and Agence Française de Développement.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) also has worked on securing swap line arrangements with other central banks that buffer external repayment risks. These include a $400 million swap line with the Reserve Bank of India, which has been approved, and a $1.5 billion equivalent swap line in renminbi with the People's Bank of China.

While such measures do temporarily boost foreign exchange reserves, they are time-bound and represent a liability to the monetary authority. They do not meaningfully increase foreign exchange reserves as do non-debt-creating inflows, such as export receipts or foreign investment, either portfolio or direct.

We expect that Sri Lanka will reorient some of its external funding to multilateral and bilateral creditors. At this stage, beyond the immediate term, Sri Lanka has not fully secured financing from official sources to cover repayment needs.

Fiscal deterioration predates coronavirus shock, magnifies its effects

Sri Lanka's fiscal position was already deteriorating before the ongoing domestic and external shocks. We expect the shocks to further weigh on Sri Lanka's fragile fiscal position, as indicated by widening budget deficits, a growing debt burden and weakening debt affordability.

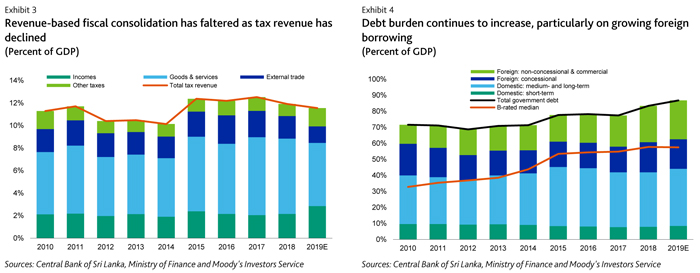

Government revenue weakened further in 2019, declining an estimated 1.5% from 2018 on slower economic growth and as weaker imports subdued other taxes and levies. Since 2017, government revenue has declined nearly one percentage point of GDP (see Exhibit 3), leaving the authorities with a shallower base from which to fund recurring and development expenditure.

Overall government expenditure increased an estimated 8.2% in 2019. Recurrent expenditure increased around 10% from 2018 levels, reflecting higher interest payments, public sector wages and other welfare programs. Public investment spending also rose because of the government's various ongoing development projects.

The wider fiscal deficit of an estimated 6.8% of GDP in 2019 increased the government's debt burden to around 87% of GDP (see Exhibit 4). During 2019, the government funded around two-thirds of its net financing needs externally. Nonetheless, the increase in domestic borrowing, relative to nominal GDP growth, drove the debt burden higher.

We expect the effects of the coronavirus outbreak to exacerbate Sri Lanka's growing fiscal strains. In November 2019, the government approved a wide-ranging reduction in the value-added tax (VAT) regime. These tax cuts, particularly amid even slower economic growth in 2020, will compound shortfalls in tax revenue mobilization.

We expect that the higher cost of debt, lower revenue, and greater expenditure to support the economy will widen the budget deficit to over 8% of GDP in 2020-21. The extent to which the government can prioritize, or delay, spending to contain deficits is quite limited, given the authorities' relatively rigid spending structure. Cuts to capital expenditure would further weaken growth in the already subdued environment.

Combined with slower nominal GDP growth and a weaker exchange rate, we expect the government’s debt burden will rise to close to 100% of GDP over the coming years. Debt affordability, already among the weakest of rated sovereigns, will decline further, with interest payments absorbing more than 50% of government revenue in 2020-21.

We expect Sri Lanka's authorities to face difficulties in managing the country's twin deficits amid the current turbulent environment.

The lack of an effective and credible policy response to arrest a more severe and prolonged deterioration in credit metrics would further dim prospects for reforms that would meaningfully strengthen Sri Lanka’s fiscal and external position. The delay in general elections could add to this challenge.

Modest fiscal policy response reflects limited budget flexibility

The government has allocated around 0.1% of GDP of existing spending for containment measures and cash payments to the nation's most vulnerable citizens. These measures come in addition to an extension of the first quarter 2020 payment deadlines for income tax, VAT and other taxes through the end of April 2020. Additional measures include tax exemptions for imported masks and disinfectants and price ceilings on essential food items.

The government is currently operating under its second Vote on Account through May 2020, in the absence of a full-year budget

before parliamentary elections. With these operational constraints, the government’s spending flexibility is limited in supporting the economy during the coronavirus lockdown.

Monetary policy effectiveness constrained amid limited maneuverability

CBSL's policy response to the coronavirus outbreak has centered around using a host of tools to pump additional liquidity into the banking system. Particularly with the lockdown in place and consumers largely using cash for transactions, CBSL has increased currency in circulation.

Since February 2020, CBSL has cut its policy rate corridor by 50 basis points, and lowered commercial banks' required reserve ratio on local currency deposits by one percentage point. The central bank has also lowered capital conservation buffer requirements and relaxed loan classification rules. Additionally, CBSL has required state-owned financial institutions to invest in Treasury bonds and bills to stabilize money market interest rates.

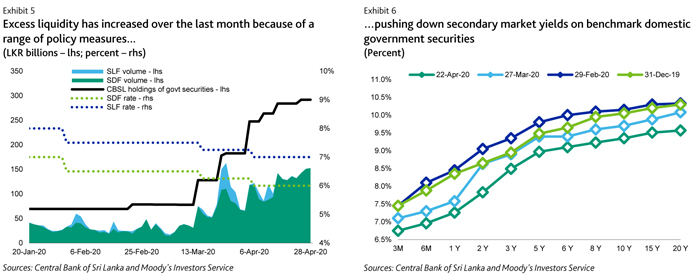

CBSL has undertaken significant liquidity injections, while foreign exchange reserves have declined by around $400 million over the course of March due to external repayments. A LKR24 billion ($123.4 million) profit transfer from CBSL to the Treasury and increased CBSL holdings of government securities have further increased systemwide liquidity (see Exhibit 5). CBSL's measures have resulted in a downward shift in the domestic yield curve (see Exhibit 6).

Credit growth will remain subdued during the lockdown period. As the economy gradually recovers and credit growth picks up, we expect demand for domestic liquidity to increase.

If external liquidity remains tight, particularly amid the sale of foreign exchange by CBSL to the government for repayment of external bonds and loans, this would further restrict monetary conditions.

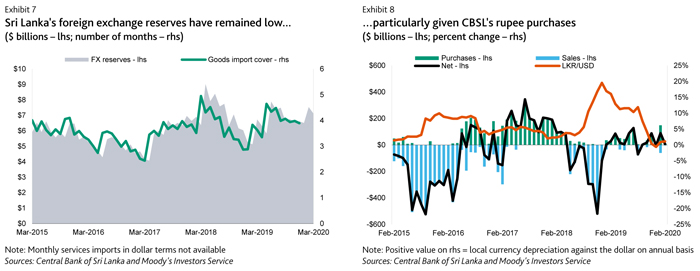

Weaker foreign exchange inflows will constrain monetary policy flexibility and effectiveness. As of March 2020, foreign exchange reserves stood at $7.1 billion, slightly less than four months of goods imports cover (see Exhibit 7). CBSL's net purchases of foreign exchange from the market in 2019 only temporarily offset weakness in non-debt-creating foreign exchange inflows (see Exhibit 8).

If external market funding remains prohibitively expensive in the second half of 2020, we except a significantly higher local borrowing requirement to fund the government’s wider deficit. Increased government borrowing, along with an acceleration in credit growth to the private sector, will push up domestic market interest rates and tighten domestic financing conditions.

Reform momentum to remain limited even after delayed election On 20 April 2020, Sri Lanka's chief elections commissioner announced a postponement of parliamentary general elections until 20 June, from the originally scheduled date of 25 April. This comes as domestic lockdown measures preclude holding an election under current circumstances.

Even after the parliamentary elections, we expect policy scope for reforms that would address hurdles to Sri Lanka's central credit challenges to be very limited for some time. Such reforms include economic, fiscal and monetary reforms that would enhance economic competitiveness, increase the government's narrow revenue base and increase the credibility and effectiveness of the monetary policy framework.

Video Story