August, 4, 2022

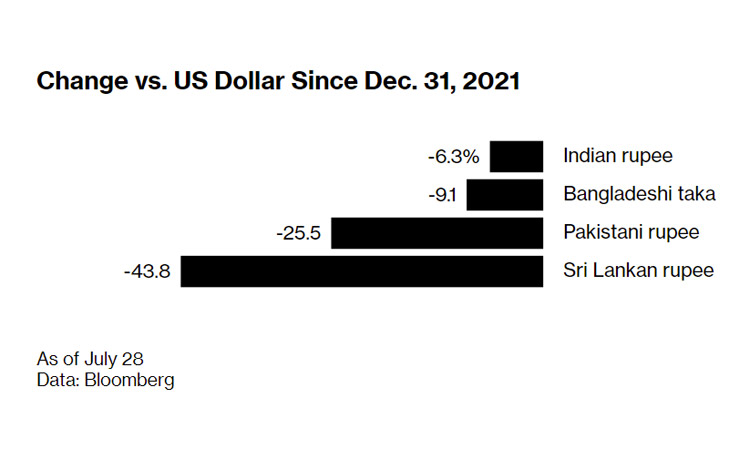

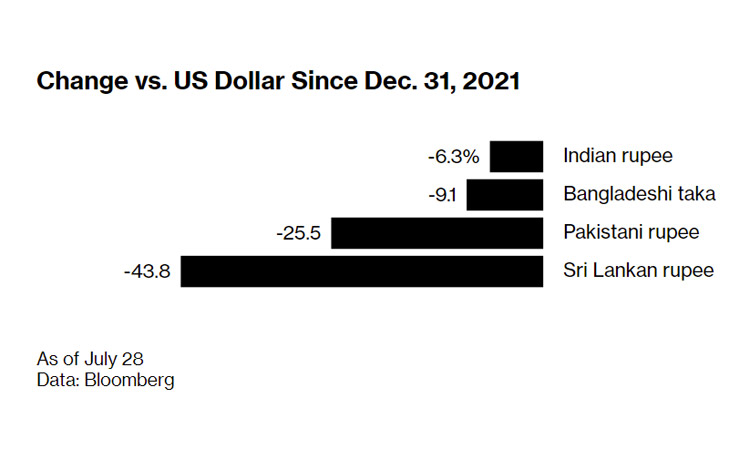

Bloomberg - Pakistan is scrambling for a bailout to avert a debt default as its currency plummets. Bangladesh has sought a preemptive loan from the International Monetary Fund. Sri Lanka has defaulted on its sovereign debt and its government has collapsed. Even India has seen the rupee plunge to all-time lows as its trade deficit balloons.

Economic and political turbulence is rattling South Asia this summer, drawing chilling comparisons to the turmoil that engulfed neighbors to the east a quarter century ago in what became known as the Asian Financial Crisis.

Back then, what seemed like an isolated event—Thailand’s July 1997 baht devaluation to cope with currency speculation—spread like a virus to Indonesia, Malaysia, and South Korea. Panic-stricken lenders demanded early repayments, and investors pulled out of stocks and bonds in emerging markets, including in Latin America and Russia, which defaulted on some of its debt in August 1998. A month later hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management, which had made highly leveraged bets on Russian and Asian securities, buckled.

Can it happen again? Ammar Habib Khan, chief risk officer at Karandaaz Pakistan, an Islamabad-based nonprofit that focuses on financial inclusion, thinks so. South Asian nations “had a big party on low-cost dollar debt, funding consumption and vanity projects during the last 10 years,” he says. “South Asia has the same vibes as Southeast Asia in 1997.”

The fault lines started to show this spring, when the US Federal Reserve accelerated interest-rate increases to combat inflation. That set dominoes falling in South Asia, where inflation has also been roaring. Easy money dried up, currencies depreciated, and foreign exchange reserves dissipated.

A prolonged crisis would sap dynamism in a region that’s home to a quarter of the world’s population and its fastest-growing major economy, India, threatening expansion plans for companies betting big on the area, such as Amazon.com Inc. and Walmart Inc.

So far, contagion seems contained. One reason is that in 1997, Asian countries’ so-called economic miracle masked vulnerabilities that are less prevalent today: too much public and private debt, weak banks, highly speculative foreign investment. South Asian countries also owe less to foreigners, having borrowed more in local currencies than in dollars to finance growth than neighboring countries did in the 1990s.

The IMF, in various stages of negotiation with the most battered economies for potential loans, also seems more forbearing. The multilateral lender imposed harsh austerity measures on flailing governments in the last crisis. This time, experts say, it’s unlikely to follow the same playbook. “I do not think there is a standard answer such as belt-tightening,” says Raghuram Rajan, a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and former governor of the Reserve Bank of India. “Indeed, poorer households may benefit from some targeted government help if we are to maintain social harmony.”

Still, there are plenty of danger signs. The region has been slammed by fuel and food shortages and the inflationary spike caused in part by Russia’s war in Ukraine. Political unrest has broken out in Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Government rationing has led to unpredictable power outages that have stretched to 12 hours a day in Pakistan and five hours in Bangladesh. “Sometimes lights go out in the evening, sometimes in the middle of the night,” says Shawon Mondol, 18, a college student from Madhukhali in southern Bangladesh, about 90 miles from Dhaka. “That’s in addition to the power cuts in the daytime. I can’t concentrate on my studies.”

Capital is fleeing. Even countries that export commodities and benefited from a strong dollar earlier this year are suffering from broad-based outflows, according to the Washington-based Institute of International Finance.

Pakistan’s currency, the rupee, has crashed to a record low and fared the worst among the countries the IIF tracks. Its sovereign debt rating is deep in junk territory. A new administration has increased diesel prices nearly 100% and electricity prices almost 50% over a few months in a bid to win an IMF bailout. Pakistan also imposed a tax on retailers to boost revenue, setting off countrywide protests. When the pandemic took hold, multilateral institutions and other countries “had a greater sense of concern for the global economy,” says Finance Minister Miftah Ismail. “That’s missing now.” He insists Pakistan is weathering the storm with the help of self-imposed budget cuts and by depressing demand for imports.

In Bangladesh, which has a steady credit rating and is considered a rising star among so-called frontier economies by many economists, fuel shortages are fomenting widespread angst and bloating import bills. The usually robust garment industry, accounting for more than 80% of exports, faces an energy crunch at home and a slowdown in orders from abroad. Bangladesh has sought IMF assistance, which officials in Dhaka say is preemptive and not to be equated with the bailout funds sought by Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Sri Lanka’s problems are the most complicated. Its government toppled amid widespread protests over fuel shortages and government mismanagement. And it’s yet to meet conditions for fresh IMF aid, such as creditor agreements to whittle down existing debt. “Everybody is in queues,” says Ravith Silva, head of Motor Link Holdings, an auto engineering company in Colombo. A barrel of engine oil that two years ago cost 150,000 to 200,000 Sri Lankan rupees ($414 to $552) now fetches one million, he says. Paint prices have risen almost 900%. “Prices are changing so fast that we cannot give a quote that is valid for more than three days.”

Sri Lanka is negotiating with China for as much as $4 billion in aid, including a restructuring of a $1 billion Chinese loan due this year, Palitha Kohona, Colombo’s ambassador to China, told Bloomberg Television on July 15. Some 10% of Sri Lanka’s external debt is owed to China, he says.

The hope is that India can provide an anchor of stability, as China did for East Asia a quarter century ago. India’s foreign currency reserves have increased twentyfold since the previous crisis, which largely spared the nation. Its stock markets have zoomed as investors placed bets on its vast consumer market. But the rupee’s fall against the dollar alongside Fed tightening has put fresh pressure on India’s ability to finance imports that have grown more costly with a weaker currency.

The central bank, the Reserve Bank of India, has been forced to use part of its war chest of about $600 billion after investors pulled out almost $29 billion from domestic equities this year, though it still has enough to cover imports for about nine months. The RBI has raised interest rates and is expected to tighten more to bring inflation down, with Governor Shaktikanta Das promising a soft landing. A neighborhood of more than 1.5 billion people can only hope for the same.

—With Arun Devnath, Kathleen Hays, Vrishti Beniwal, Anup Roy, Tom Hancock, Enda Curran, Karthikeyan Sundaram, and Asantha Sirimann

Video Story