February, 29, 2024

By Dr Asanka Wijesinghe

Thailand became the second Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) economy to sign a free trade agreement (FTA) with Sri Lanka, following the FTA signed earlier with Singapore. A major goal of an FTA is to lower trade costs by reducing border tariffs and eliminating behind-the-border barriers for competitively traded products. This article assesses the coverage and potential of the Sri Lanka-Thailand FTA (SLTFTA) tariff liberalisation in increasing bilateral trade.

Coverage of the SLTFTA

Salient features of the SLTFTA tariff schedules include immediate concessions for a limited number of products, a 15-year phased tariff reduction plan for most of the products, and uncommitted products which are excluded from any commitment for tariff reduction or elimination. Notably, the tariff liberalisation programme is not limited to custom duties, but also expands to para-tariffs.

Given that 25.6% of products are already under zero tariffs in the case of Thailand, the SLTFTA commits to reduce or eliminate tariffs on 59.4% of products for Sri Lanka. Thailand provides immediate concessions for Sri Lanka over 2,188 products, while tariffs on 4,597 products will be subject to phased reduction within 15 years. Thailand’s uncommitted list includes 1,708 (or 15% of products).

By contrast, only 17.4% of products are under zero tariff currently in the case of Sri Lanka, implying that Sri Lanka will reduce or eliminate tariffs on 67.6% of products through the SLTFTA. Under the agreement, Sri Lanka commits to immediate concessions for 2,722 products (or 33.4%), reducing or eliminating tariffs on 2,796 products within 15 years, and maintaining 1,224 products on the uncommitted list (15%). By the end of the tariff phase-out, both countries will have 85% of products under zero tariffs, or tariffs liberalised under the SLTFTA.

Figure 1: Distribution of the value of imports by Sri Lanka and Thailand over different tariff groups (2022)

Source: Authors’ Illustration

Although both countries will maintain about 15% of products in their uncommitted tariff schedules, the corresponding import values are largely uneven (Figure 1). Based on 2022 values, Sri Lanka’s uncommitted list covers 39% of imports from Thailand while only 4% of imports from Sri Lanka are covered by Thailand’s uncommitted list. Sri Lanka excludes major Thai imports like sugar, cement clinkers, many rubber products in HS chapter 40, food imports like seafood, manioc, red onions, lubricants, and cotton in the uncommitted list. The import-competing industries and revenue considerations incentivise Sri Lanka to retain policy flexibility in setting tariffs for these products. Notably, as seen in Figure 1, Sri Lanka exports 74% of products by value under zero tariff in pre-SLTFTA.

The Offensive Lists: A Closer Look

The effectiveness of an FTA hinges on offensive lists – products with a comparative advantage and potential for expanded trade. A recent IPS study identified 147 six-digit HS codes as Thailand’s offensive list and 154 six-digit HS codes as Sri Lanka’s offensive list.

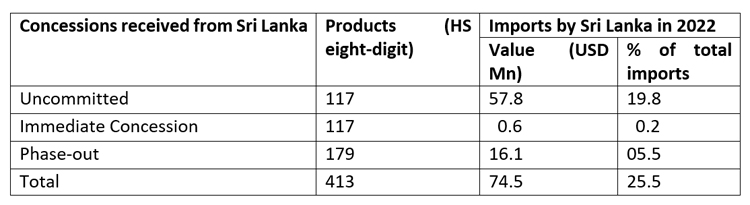

Under the SLTFTA, of the 147 six-digit codes in Thailand’s offensive list, Sri Lanka’s tariff schedule contains 413 products at the more disaggregated eight-digit HS codes (Table 1). As such, Thailand will receive tariff concessions for 71.7% of these offensive list products. However, some of the offensive list products are in Sri Lanka’s uncommitted products list – although just 117 in number, they account for USD 57.8 Mn or 19.8% of Sri Lanka’s imports from Thailand in 2022.

Table 1: Distribution of products in Thailand’s offensive list as per SLTFTA concessions

Source: Authors’ calculations.

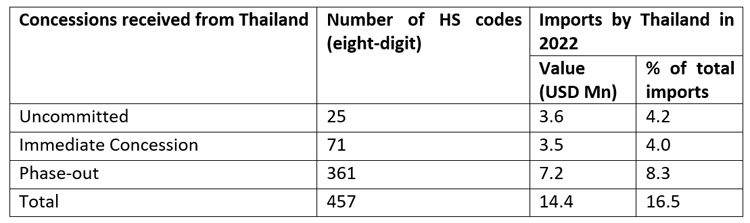

Similarly, of the 154 six-digit HS codes identified as Sri Lanka’s offensive list, Thailand’s tariff schedule contains 457 such products at eight-digit HS codes. Unlike Sri Lanka though, only 25 such products are on Thailand’s uncommitted list, accounting for 3.6% of Thailand’s imports from Sri Lanka in 2022. Additionally, although Thailand puts 12 ready-made garment products (USD 3.6 Mn or 4.2% of imports) from Sri Lanka’s offensive list in its uncommitted list, 130 offensive list products (USD 3.6 Mn or 4.2% of imports) from HS chapters 61 and 62 will see tariffs phased-out. Out of these 130, Thailand did not import 68 products in 2022 from Sri Lanka.

For Sri Lanka, the immediate concessions given for offensive list products include tariff rate quotas for desiccated coconut, green tea, and black tea. Provided that Sri Lanka has a high comparative advantage in tea and desiccated coconut, and the existing high tariffs on these by Thailand, the quota under SLTFTA is a relatively positive outcome for Sri Lanka. However, the quantity under the tariff rate quota can be quite low and efficient distribution of quotas might be administratively challenging.

Table 2: Distribution of products in Sri Lanka’s offensive list as per SLTFTA concessions

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Dissecting the SLTFTA: Potential for Increased Bilateral Trade

The substantial coverage of the SLTFTA, binding commitments for phase-out tariff reduction, applying tariff reduction to para-tariffs, and a tariff rate quota for Sri Lanka’s tea are positive features. Both countries receive tariff reductions or elimination for the majority of each country’s offensive products. However, the strategic use of uncommitted lists to restrict imports from the partner country may weaken the effectiveness of the FTA. Sri Lanka's uncommitted list notably includes rubber products, ceramic tiles, sinks, washbasins, ceramic tableware, soaps, detergents, beverages, and sugar and confectionery items, reflecting existing trade distortions and suggesting limited potential for FTAs to address incentive distortions. Yet, given the political challenges of a comprehensive tariff overhaul, limited liberalisation through FTAs emerges as a viable second-best option for policymakers.

Similarly, Thailand excludes vital ready-made garment products and agricultural products like tuna and black pepper from the SLTFTA tariff liberalisation. However, the exclusion is limited to 25 offensive list products of Sri Lanka.

Overall, the potential for a swift increase in bilateral trade in already traded products is low given that immediate concessions cover a lower percentage of products, and the major currently traded products are already under zero tariffs. However, the SLTFTA removes bilateral tariffs on competitively exported products by both countries, opening a window for increased trade over time. Currently, many products in the offensive lists which get tariff concessions under SLTFTA, are not traded bilaterally.

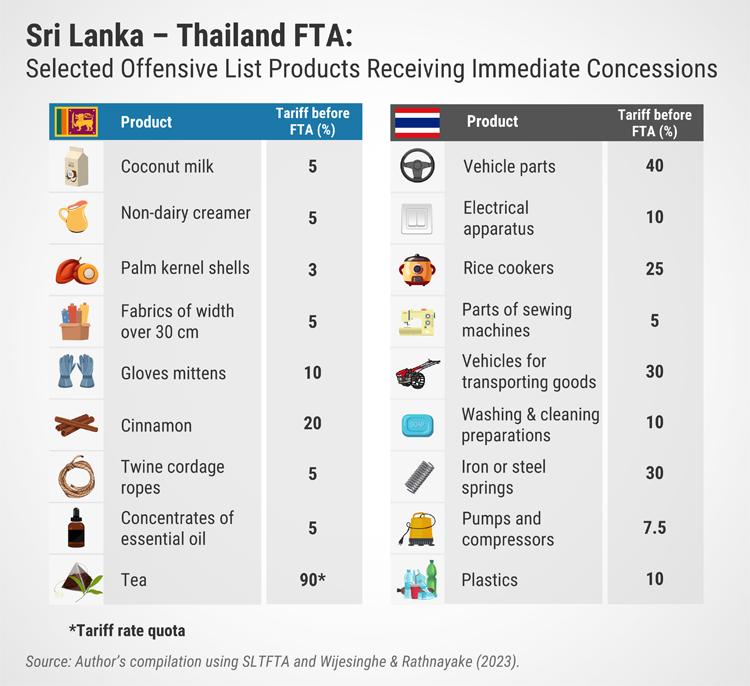

The trade effect of SLTFTA may come from trading new products that were not traded bilaterally before the FTA due to bilateral trade frictions. Accordingly, products in the offensive lists that receive immediate concessions are better candidates for increased bilateral trade (see Infographic). Dissemination of accurate information on tariff concessions, and eligibility criteria including rules of origin, linking exporters to potential buyers through market facilitation, and investment promotion may increase bilateral trade in these products.

Infographic: Sri Lanka – Thailand FTA: Selected Offensive List Products Receiving Immediate Concessions

Link to original blog: https://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2024/02/28/unlocking-trade-potential-how-the-sri-lanka-thailand-fta-paves-the-way-for-enhanced-bilateral-trade/

Dr Asanka Wijesinghe is a Research Fellow at IPS with research interests in macroeconomic policy, international trade, labour and health economics. He holds a BSc in Agricultural Technology and Management from the University of Peradeniya, an MS in Agribusiness and Applied Economics from North Dakota State University, and an MS and PhD in Agricultural, Environmental and Development Economics from The Ohio State University.

(Talk with Asanka - asanka@ips.lk)